Yossi Sassi Talks Heavy Metal Makams

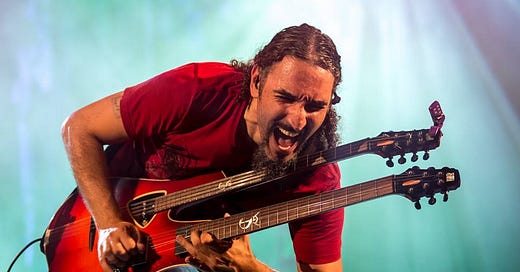

The Israeli shredder creates an organic, if heavy, synthesis of East and West

Whatever you did during the pandemic, it probably wasn’t as cool as what Yossi Sassi finagled. The Israeli guitar legend packed up his eight-piece ensemble, the Oriental Rock Orchestra, and spent a week in isolation on the Greek Island of Santorini.

(I spent 13 months—and counting—in the Brighton neighborhood of Boston. How about you?)

It was in that secluded, cutoff environment—without distractions—that the group recorded their latest release, Hear and Dare (hot off the presses, March 19), and that island vibe was conducive to the looseness and group interplay Sassi was after.

“I wanted the musicians to experience what they experienced and to react in real time,” he says. “I wanted to capture that very virgin authentic feeling from the musicians when it happened. That’s something we succeeded with greatly on this album.”

Sassi has been recording and touring the world for more than 30 years. He first rose to prominence with his band, Orphaned Land, which pioneered the Middle Eastern heavy metal fusion sub-genre. Orphaned Land fused elements of metal and shred with the Arabic and Mediterranean scales and sounds Sassi grew up with. That unique approach, combined with the band’s universalist ethos and message of positivity and coexistence, earned them legions of fans throughout Europe and the Arab world.

It also established Sassi’s reputation as Israel’s premier shredder, which led to him sharing stages and collaborating with a who’s-who world class guitarists like Steve Via, Marty Friedman, and Ron “Bumblefoot” Thal.

“I started working about a decade ago on instrumentals outside of Orphaned Land,” Sassi says. “That’s how I hooked up with Marty Friedman. He came to Israel. I was this so-called Israeli guitar hero, and he really loved that. He heard it from the production and he wanted to invite me to the stage, and that turned into a beautiful friendship. We’ve since toured together, and my band members became his band members for a while. Marty was the first known guitar player I toured and recorded with. That followed with Bumblefoot—also a good friend for many years—as well as Steve Vai and even Joe Satriani. I was lucky enough that all the guitar players I had posters of in my room when I was growing up I eventually ended up collaborating or performing with. I feel I am still fortunate to be living the dream.”

I spoke with Sassi from his studio in Israel. We spoke about his trip to Santorini—as well as the video for the title track, “Hear and Dare,” that was partially shot there, and which recently premiered on the extreme metal site, Decibel—as well as his history and experiences with Orphaned Land, his intuitive embrace of Arabic makamet, building bridges with music, and how, for him, music is a spiritual experience.

What was your introduction to music?

My romance with music started before I was born. My late grandfather, may he rest in peace, Yosef Sassi—the original Yosef Sassi, he died at age 94 a few years ago—he was a rabbi and a cantor (חזן) in a synagogue in Herzliya. He was a man of Torah. Music and his faith, those two pillars guided his life. He played the oud and some bouzouki, and he knew very deeply the makamat, the circuits of Arabic chanting [makam, or plural, makamat]. He knew the Eastern as well as the Western scales, but more leaning toward the Eastern scales. Growing up, my father, David—he is number four out of 10 brothers and sisters—and his family was all about learning Torah and playing music. There was one guitar in the house and everyone played it. They all grew up to be musical to one extent or another. Me, being the eldest grandson—I took his name—I also grew up with a lot of those influences at home. Music was always around me.

My father is a big music lover, and we had Greek, Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Turkish music, and also Tehillim [Psalms], Piyutim [liturgical melodies]—that was all part of the culture at our house. My father used to always sing at home, and at least once a week he went to a regular gathering at one of the synagogues in Herzliya. I joined a couple of times, too, and it was really fun. That was something that was absorbed in me since early childhood. Little did I know that later on it would catch up.

When I first touched the guitar at around bar mitzvah age, the first tunes that came out when I started to play something decent, leaned towards the Eastern scales. It was a lot of elements from the Piyutim, and from the music from the different countries in the region around us. So even when I play rock and blues and metal, I have this touch. Naturally it evolved and got refined throughout the years, but that has defined my musical style since the beginning. It’s this blend of East and West, acoustic and electric, and, in a way, past meets current and future. I really love this fusion of styles.

That fusion is very popular in Israel these days, but you were one of the first.

Right, we did it quite early. That was with Orphaned Land, my first band, which we started in 1991, and I was a member for 23 years. I was the lead guitarist and musical director. I was basically the main composer during those years, and we basically defined the genre. Oriental metal was something that didn’t exist before Orphaned Land. With my guitar playing outside of the band, too, in collaborations with other artists as well as my solo group. Although that is more Oriental rock, it is a bit less heavy. It's less metal, but still a clear fusion of East and West, acoustic and electric.

When did you start picking up other instruments in addition to guitar? I read that you play 19 different instruments.

I do. I play 19 different types of stringed instruments, most of them traditional folk instruments from different countries I’ve visited during our different tours. I love stringed instruments. All music is amazing and great, but for me, strings have a special appeal. On the one hand, they have the features of an acoustic instrument, with the wood and the different materials of the strings themselves. Strings are very delicate and prone to changes in the atmosphere, humidity, and the temperature in the room. But at the same time, they are quite dynamic. The flukes and timbre of those instruments are so versatile that when you master them, you can produce very specific levels of velocity and dynamics as opposed to something more static like keyboards. Piano is an amazing instrument, too, but still, strings are my big love. Until today, I am excited about any new stringed instrument I get into my hands.

On your guitar, you have a floating bridge, but no whammy bar, and you’ll lean on it when doing certain bends. Is that so it’s easier to play microtones, or notes not found in Western scales?

That technique is one of the techniques I use to create vibrato without the handle on the tremolo bridge. To do the quarter tones, that has a lot to do with the bends and also with the left hand. By now, I don’t think about that at all. It just comes out naturally.

Do you just hear it and hit the right spot with the bend?

Yes. I discovered early on that I have absolute pitch, so that helps. For better and for worse I know exactly where I am with every note that I play [laughs].

You mentioned the makamat. Have you studied those systems or do you use them more like modes, as vehicles for improvisation and composition?

I learned them at home with my father and grandfather. But I am just a street cat when it comes to music education. I learned it as life occurs. I didn’t learn it in a school. When I play, I am more drawn to makamat than Western scales. It is interesting, because when I try to explain my songs—when I get interviewed in guitar magazines or in workshops—I speak using the diatonic scales and Western terms and modes. I'll say harmonic minor as opposed to say, Hijaz [laughs]. Deep down I think in makamat and I play in makamat. Even though you see a dude with long hair and an electric guitar, I play makamat. What you see in my hands is the closest thing I found to makamat on a Western instrument that has diatonic tones and a semitone structure. I think in makamat and I play in Western scales. But the ambition of the note is always to sound like it is inspired from the makamat. In the head, that’s what’s happening.

It’s like a synthesis of East and West.

Right, and people can experiment with that. I am doing it automatically. It’s uncontrollable because makamat and those sounds were in my childhood way before Metallica. In those crucial years, from age zero and five and 13. My brain is wired that way, but you can do an experiment. Play a tune or solo or even just a scale on guitar. Try to think of every note you play as you go along as hitting the closest note in that makam, to that quarter tone or to that similar tone. They are not exactly the same scales, but they are quite similar in many of their notes.

Meaning what, that say, you’ll play a dorian mode with a flat two and that has a somewhat parallel makam? You’ll play that, and bend the notes in that mode until it sounds like the makam?

Right, sort of the closest to it.

Your message—both with Orphaned Land as well as in your solo career—is about mutual respect, coexistence, and using music to transcend differences. But as an Israeli, have you also had to deal with negativity, or does your message and music overcome that?

Music is a language, and it is a language we all share. Everywhere I go in the world, maybe I don’t speak the spoken language, but do re mi is the same. Notes are notes. That really helps to build a bridge between different opinions and beliefs. In general, that message was really well accepted. I don’t know if it would have been if I was not a musician, and definitely, that road didn’t come without bumps along the way. We had some events of hatred. Some of them have been passive—luckily most were passive—and some were a bit more active. We had some experiences of antisemitism in Mexico when doing some touring, and a few in Europe in Strasbourg, on the border between France and Germany. It’s always there. Being an Israeli or a Jew and being open about that, that’s something that at some point somebody will want to say something about. However, in 30 years of professional music, it’s something that’s [rarely happened]. It is side phenomena when compared to the rest. Bringing hearts together and bridging between people, that’s really 99.99 percent of what’s happening most of the time.

Your double neck guitar, the Bouzoukitara, is a guitar and a bouzouki. Why specifically those two instruments?

The Bouzoukitara was born from necessity. I had a real need in live shows to switch between electric guitar, acoustic guitar, and bouzouki, which is a greek mandolin. Many years ago, I took those three different instruments on the road with me and tried to switch between them in live shows. I had to find a more effective way to do that. With the help of the guitar builder, Benjamin Millar, it became a reality, although not without struggles and mishaps along the way. We had to fix a lot of things and figure them out from the initial prototype, but I am proud of the result. It is my go-to tool, especially for live shows. I use it in the studio, too, and I am happy with how it turned out.

But why bouzouki? Why not, say, oud-guitar or something else? Is bouzouki your main non-guitar instrument?

I think it’s something with the bouzouki’s tonality. The oud has an amazing sound, too, but it is a more niche, specific sound. The oud immediately takes you to the Middle East, the desert, the pyramids. The bouzouki is more Mediterranean and less Arabic. It takes you to many other places. You can play anything from metal to folk to classical music. You can have a bouzouki playing with a piano. When I thought about it—it was a Pareto 80/20-type thing—I went with the bouzouki. There’s also the fact that I enjoy playing that instrument.

Your new album, Hear and Dare, was that recorded in Santorini?

Yes. Santorini, which is in the Greek islands. It is my fifth studio album with the Oriental Rock Orchestra, and recording it was really a unique experience. The way this album happened was that when we started, none of the players knew what we were going to play. Plus, in between quarantines and lockdowns, it was a last minute thing. Twenty-four hours before we flew, we didn’t even have clearance to leave the country. We came to the island, and went to this facility, Black Rock Studios in Santorini, which is a top notch studio. You gaze into the sea while you are recording. It’s a villa that has all the facilities—food and beds and stuff like that—we lived in the place for a week. We woke up every day, ate well, and then I would sit on the balcony and teach the band the elements of the songs. I would play it for them. They would pick up pieces of it, and adjust it. The final arrangement happened on the island.

We would go into the studio and record together as a band. We didn’t use the approach that’s been dominant these last few decades, which is work on the grid, put a click, and record the drummer first, then the bass player, then after the rhythm section record other musicians in layers. We entered the studio and played songs that were freshly learned. I think that magical experience is something that really contributed to the sound of the album. I honestly think I could never have recorded something similar in Tel Aviv, or in our hometowns, coming in and recording. When you go the studio in New York City or Tel Aviv, the musician comes and says, “I have two or three hours.” He puts a parking app with a notification. He tries to learn the part—or will listen to them in advance to come prepared—and I didn’t want that. I wanted the musicians to experience what they experienced and to react in real time. I wanted to capture that very virgin authentic feeling from the musicians when it happened. That’s something we succeeded with greatly on this album.

You recorded most of the album live as a band, with very few overdubs?

Exactly. I was counting on the maturity of the musicians, and their fantastic musicality. It’s eight people playing together. The vocalists were the only ones we recorded later. We listened a lot to each other—because the only way a song can sound this full and whole, but at the same time not too cumbersome so you can enjoy it—is when the musicians listen to each other. Each person knew when to step down and when to let someone else shine. That’s something that I produced in very little touches on the island.

What were the compositions? Were they sketches your brought with you to the album or complete pieces?

The compositions were ready. I had the songs composed before coming to the island. Some songs had a final structure that I felt was how the song should be. Some of them were a bit more loose. They had more places for interpretation and personal expression. Two of the songs were more jammy in a way, but I don’t know if you’d be able to recognize them as jams. Maybe one. The other doesn’t sound like a jam at all, it sounds like a deliberate pre-composed effort. That’s some of the beauty of it.

We talked about bringing East and West together harmonically, but how about rhythmically? Are you trying to fuse those rhythmic elements as well?

In that sense rhythm is very important to me. I always say that secretly, deep inside, there is a silent drummer in me [laughs].

Isn’t every guitarist a frustrated drummer?

I don’t know, but for me, percussion and having a deep rhythmic understanding is something that’s so important for me as a guitar player. I am drawn to different beats—Moroccan, North African, Iraqi, Turkish, Balkan—there are many great Balkan patterns and rhythms. Some of them, like Aptaliko—Zeibekiko is the general term for this type of Greek folk music, and Aptaliko is the beat—I wrote songs around that. There are songs I wrote where I wanted a specific rhythm, and I took the rhythmic pattern and around that I wrote the melody. It comes down to that. I sometimes think about the rhythm before I think about the rest of the music. I want to have a specific element and I pursue that. It can be specific rhythms from places around the globe and different cultures, but it can also be because I want to write a song in, say, 5/4. One of the new songs on the new album, “Gates of Ishtar,” which we called “Five” in the recordings, because it is in five. I came up with a cool guitar riff in 5/4. The five is the feeling that matters, the riff is secondary. The rhythm is what matters for many of the compositions.

From growing up with your grandfather, and your early experiences with Piyutim, do you find there is a spiritual nature to music? Do you see music as part of your spiritual practice and how you find yourself spiritually?

Definitely. I look at music as the closest to God that we can get. At least speaking for myself, it’s the closest I got. To be honest, when I play—it doesn’t matter if it is in the studio or live—I am not there. It is the only thing I do in life that sometimes, when I try to recap what happened, I don’t remember. It is that spiritual and holy and different. Some things I play or do, or the way I do them, [descend] from this other frequency that is less produced. It is a very natural and whole place, and highly spiritual.

But with that said, I think people tend to look at spirituality as this thing in the air or as very vague. I think it is the contrary. Being spiritual for me is being very well connected. It’s being realistic. It’s being one with nature or one with the here and now, and understanding the here and now, and understanding your limits as a human being, as an organism, as part of the huge nature around you. That really gives you a sense that’s a mix of humble and unique. When you feel one with creation, that’s what spirituality helps you get, whether it is through music or prayer or anything you choose. Because at the end of the day, whether it is God—or what the Catholics call the Trinity or the Muslims call Allah—we all understand that inside, everyone means the same feeling. It’s different names for the same feeling. For me, it can be guitar playing. For me, when I play the guitar I am in a humble and very elevated state. That is the duality I feel.

It reminds me of the story. I don’t know the correct reference [it’s from the early Hasidic master, Rabbi Simcha Bunim of Peshischa]: A man should carry two notes in his pocket. One says, “The world was created for me.” The other one says, “I am just dust and ashes.” I come from earth and I go back to earth and I am nothing. I think being able to balance that, that’s something that spirituality gives you. To always be humble, but at the same time understand that we were all meant with potential for greatness, and what we do with this trip, this time we are given, and what we make others feel while we are at it, that’s what counts.

Photos courtesy Yossi Sassi

From The Archives: #ICYMI: Mr. Multifaceted

Multi-Instrumentalist Koby Israelite talks about doing everything, and more

Read the full interview with Koby Israelite here.

Subscribe To Our Premium Tier. $5/Month Or One Year For Just $50

Subscribe now to our premium tier. It’s just $5 a month or $50 for an entire year (that’s two free months!).

The premium tier does not replace the great content you already receive, rather, it gives you even more.

Specifically, paid subscribers get:

Deep, probing essays about the spiritual nature of music.

Incredible curated playlists. These playlists include more than just music from the artists featured in the Ingathering, but also things we stumble upon in our research, and amazing things we need to share. If you’re a paid subscriber, you’re someone who needs to hear this.

The opportunity to support the Ingathering. The Ingathering is fun to produce, but it takes a lot of effort and time to research and write. A paid subscription is an amazing way to show your support.

Become a Founding Member. If you love the Ingathering, and you’re looking for a way to show even more support, become a founding member. The suggested founding donation is $180. You can give less if you want—as long as it’s more than the cost of an annual subscription—and obviously, you can always give more. The amount is up to you.

If you’d rather just give a donation, you can do that, too. The Ingathering is a project of Vechulai, a registered 501(c)3 tax exempt organization. Go here to donate and learn more. You can also Venmo us @Vechulai

If you don’t want to be a paid subscriber, that’s not a problem. Stay a free subscriber and keep enjoying the great content you already receive.

The first premium newsletter, “Music, Community, and Prophecy,” went out last month, and it was amazing. But you need to be a paid subscriber to read it. Don’t miss out.

As always, if you have any questions, hit reply and we’ll get right back to you (or email us at: jewishmusicandspirituality@gmail.com).

Thank you being a regular reader and part of the Ingathering family. Your support at whatever level—founding member, premium subscriber, or free subscriber—is invaluable, and we can’t do it without you.

Thank you!