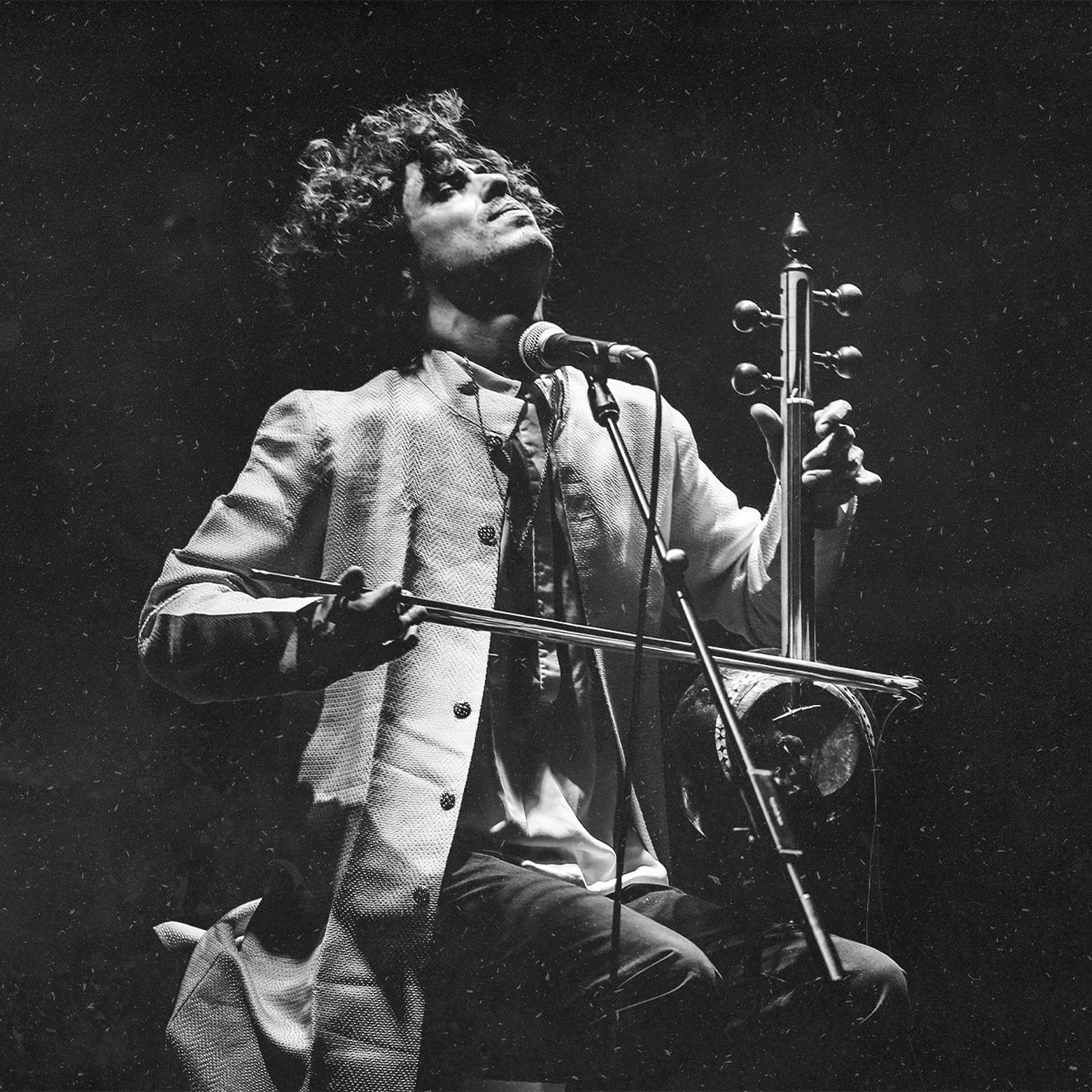

Mark Eliyahu Is On The Fence, And That’s Fine With Him

The composer and multi-instrumentalist stands at the crossroads of east, west, ancient, and modern

Multi-instrumentalist and composer, Mark Eliyahu, lives at the intersection of east and west. His music is a multicultural mashup, and transcends genre and culture. “Music for me is universal,” he says. “I don’t see music as genres. If I connect with something in music, it doesn’t matter to me where it comes from or what genre it is. Music is music.”

That universality is Eliyahu’s animating spirit. He grew up in a musical home, surrounded, at least at first, by classical music, which included everything from the old masters to the contemporary avant-garde. His musical horizons expanded as his father, noted composer and musicologist, Piris Eliyahu, began studying Persian, Caucasian, and other Central Asian classical styles.

Everything, seemingly, made an impression, and as an early teen, Eliyahu took up bağlama, which is a long-necked/small-bodied guitar-like instrument, also known as the saz. He left home at 16 to study bağlama in Greece, but six months later, after discovering the kamenche—a bowed instrument, similar to a violin, and played upright like a miniature cello—left to study for two years in Azerbaijan, where he immersed himself in the makam-based Iranian and Azeri classical music traditions.

But despite that pedigree, don’t think Eliyahu is an acoustic-only purist. His omnivorous tastes are broad, incorporate old and new sounds, and fuse traditional elements with things like computer-generated rhythms, and digital processing.

“In the last three or four years, I started to add some electronic elements to my music and scores, and to the original music I compose for films, and also pure electronic stuff,” he says. “It’s also part of me and part of my expression. It’s natural for me.”

Eliyahu has been performing, studying, touring, and recording for 20-plus years, and has amassed an audience, which, like his musical tastes, is borderless. He lives in an idyllic, rural environment—his studio is inside a yurt, and sits in a lush, green, wooded area—and is working on new music and recording.

I Zoomed with Eliyahu—he hung out in front of his yurt as the sun set in the background, while I was in Boston, enjoying yet another blast from the Arctic—and we spoke about his incredible experiences studying music, his polyamorous relationship with technologies and genre, his magical 150 year old kamenche, and how living in Israel is central to his music and journey.

Did you start studying music before your family left Dagestan?

I started my musical studies when I was four. I started with the classical violin, and I played and studied violin until I was about 14. Both my parents are musicians. My father is Piris Eliyahu—he’s a known composer all over the Middle East—and my mother is a pianist, Larisa Eliyahu. I grew up in a musical family, and there were musical events at our home. When I was about 13 years old, I discovered the bağlama, which is also called the saz. I couldn’t find a teacher here in Israel, so I practiced by myself and my father showed me some stuff from his knowledge.

When I was 16, I left my home and friends and family and moved to Greece to study the saz with a known master named Ross Daly. I had a lot of lessons every day. I learned Turkish and Greek music, and another instrument called the tambour. While in Greece, at Ross’s home, I discovered the kamenche for the first time. I was fascinated and blown away. It was like a mystical moment. I felt with all of my body that I was in love with its sound. I felt that it was a sound that I had heard inside myself since forever, although it was the first time I heard it with my ears.

I called my father and told him that I just had this mystical experience hearing the kamenche. I told him that I had to find this instrument. He was very surprised, and told me that my great grandfather—his grandfather—was a kamenche player. So it’s like it was meant to be. It felt like karma, goral [גורל, or destiny], and so from Greece I moved to Azerbaijan when I was 16 and a half—I did half a year in Greece and then moved to Azerbaijan for two years—and in Azerbaijan I studied kamenche, as well as Persian and Azeri classical music.

After that, I kept traveling—already as a performer and composer, I created my show—and continued studying from different masters all over the world. I spent another half a year in France and studied with a great master from Iran, his name is Hossein Omoumi, and learned Persian classical music. Of course, my main musical teacher is my father. The whole time he’s guiding me. He’s my mentor, and also as a teacher. My first stages as a musician were with my father. He took me as a young person into his band and with different orchestras and different masters from all over the world. We’re still playing together now.

Your father plays the tar. Is that similar to the bağlama?

No. It’s very different. It’s a different tuning and a different technique. Also, culturally they’re different. The bağlama is mainly played in Turkey, Greece, and also Mongolian areas. Tar is more Persian, Caucasian, and Central Asian. There are cultural distinctions, although there are similarities between them, too.

Azerbaijan is next to Dagestan. Did you visit while you were studying there?

No. I had so much passion to go visit. I was young, and it was very dangerous at that time in Dagestan. I don’t know about today, but at that time, the Chechnya situation was happening with Russia, and it was dangerous to go there.

What were you studying with these different masters?

We basically learned makams and the classical music of Iran and Azerbaijan.

Is a makam different from a scale?

It’s like a scale and it’s also like modes, and there are some movements inside these modes. Like Greek modes, makams are similar to those. There are also scales, movements inside the scales, the feelings, and the main notes that they’re based on. You can have two makams on the same scale, but different feelings.

Are certain makams assigned to work together?

The traditional way is strict. There are makams that are from the same family, and there are so many. There are 12 families of makams, like the 12 months in a year. Each family has a different color and a different vibe. In ancient times, there was also a medical usage of makams. There were hospitals and they healed with makams. The last one was in Bagdad about 200 or 300 years ago, the last one that was known.

Is a makam a tool for improvisation or is it only a compositional tool?

It’s for improvisation based on specific movements. It’s like a bible that you learn by heart—specific melodies that are not based on a rhythmic cycle—you learn specific melodies, and you have to know them by heart. You play them for many years, and the goal is to then forget them and improvise. When you are improvising, because this is your base, you can improvise in the right way. It’s different than if you have a scale and improvise whatever you want. You have some guides that guide your improvisation, like where to go, where to stay, and where to scream. After many years, you forget it and just improvise from your heart. But when someone from the tradition listens to you, he understands that you’re doing something more deeply than just free improvisation.

In your music, do you use these makam systems and stick with those rules or do you do what you want?

With the years, I do whatever I want. I forget where I am, which scale I am using. That is the best point of creation for me, when I don’t know where I am specifically. I just say what’s inside my heart. I feel that with the years I can express my own stuff. It is not makams—it is not similar to any tradition or any genre—but at the same time, it is one foot in a deep tradition and another foot in the future and discovery and more modern sounds.

You do electronic dance music, too. How does that work rhythmically? EDM usually has a straight, 4/4 pulse, and these other musics have very different feels.

I am coming from a lot of places. My early education was classical Western music: Chopin, Bach, Mozart, and all of that. My mother is a classical pianist, and my father wasn’t playing tar when I was a kid. He composed modern Western music, like modern and post-modern, 20th/21st century music for different orchestras and stuff. I grew up with more classical vibes and education at home. But as a kid and as a young person, I was also listening to pop like everyone else—mainstream music and rock—and I had a long experience with rave parties and psychedelic music. At the same time that I was learning the saz, I was listening to psychedelic rave music and going to parties. I was influenced from many different things. I also did mainstream Israeli and Turkish pop, and so I am not coming from a traditional place. I learned makams for many years and I understand what’s going on there, but at the same time, I feel classical vibes in my music and I bring the Oriental stuff into it. My base is not traditional.

In the last three or four years, I started to add some electronic elements to my music and scores, and to the original music I compose for films, and also pure electronic stuff. It’s also part of me and part of my expression. It’s natural for me. Also this straight 4/4 pulse, that’s natural for me, too, and it is simple. I love simple stuff. Music can be simple. When it’s simple you can add more feeling and more of your heart and soul. I don’t have problems with 4/4. I love it. It’s cool.

Was it hard to internalize those other rhythmic feels?

No, that was also natural for me, because I live in the Middle East. I grew up on the Oriental, and also at weddings and family events. We have these rhythms, too. It wasn’t so difficult, it was very natural for me.

I’ve seen videos of Andalusian orchestras, and in those, the violinists play their instruments on their lap. Is that like their version of the kamenche?

In North Africa—in Morocco, Algeria, and Libya—they play the violin that way. In Arabic, they call the violin, kamenche. The kamenche was also used in Arabic music. You can see it in Iraq—they call it joze—and also in other Arabic cultures, but more in the folk way with less strings called the rabāba. They had the kamenche many years ago, and when the violin came, many musicians left kamenche and used violin instead. But they still call it kamenche.

Do they play it on their lap like a kamenche?

Yeah, and in Iran, too. The kamenche is an original instrument of Iran, Azerbaijan, Caucasia, and Armenia. About 80 years ago in Iran, they almost lost the kamenche, because no one played it anymore. All the players switched to violin, because it has more volume and more presence. The kamenche is quieter. Only one player, Ali-Asghar Bahari, stuck with the kamenche. Nowadays, there are many new students and players and masters, but they almost lost it.

How is it tuned?

Like an Arabic violin. Sol, re, sol, re [GDGD], which is fifths and fourths.

Do you use alternate tunings as well?

I am searching all the time, changing tunings, and trying different things to find something new and developing things. You can do what you want for music. The music is the main thing. The instrument is playing the music, so you can change and try things. Sometimes, I’ll take one string down and make it a drone. You can do whatever you want. I try stuff. It isn’t a violin that you have to play a certain way, although with every instrument you can tune and search for things. I do that.

Is your kamenche 150 years old?

Yes. I got it from a master player, Habil Aliyev. He is the same master who I told you about, from when I first heard the kamenche in Greece. It was Habil Aliyev who inspired me. He was the first kamenche player I ever heard.

And now you have his instrument?

My father got it for me from him. He gave it to me when I was in Azerbaijan. He had promised my father that he would give it to me when I grew up, many years before. He had played my father’s compositions, and my father brought him to Israel three times to perform his compositions. They were colleagues and good friends, so he promised it to my father and that’s how I got it.

As opposed to a violin, the kamenche sounds many harmonics and sympathetic frequencies in addition to the note you’re playing. Is that part of the style of how it works?

Yeah, because it’s made from skin. The belly of the instrument is skin and it resonates. The tuning, as we said, is sol re sol re, so when you play the low re, the high re resonates with it. That’s part of the instrument. The acoustics and the overtones are part of the beauty of the instrument.

You often use keyboards in your music, which are tuned to standard Western tuning. Are you careful about not clashing with the microtones from your other instruments?

I work on it. When I compose, the piano and the other instruments are a part of the composition. If I use microtones while I am playing, I make sure the piano is not playing the same notes. It’s strictly worked out, and not improvised. The songs are not charts [or lead sheets], they are specific notes and arrangements. Specifically, when piano playing and kamenche are together, they are never playing the same notes except in specific places where it’s needed.

From The Archives: #ICYMI: Global Grooves And Other Adventures

Israeli keyboardist Lior Romano talks about his various projects, as well as his new dance-friendly seven-inch.