It Takes A Village To Keep It Funky

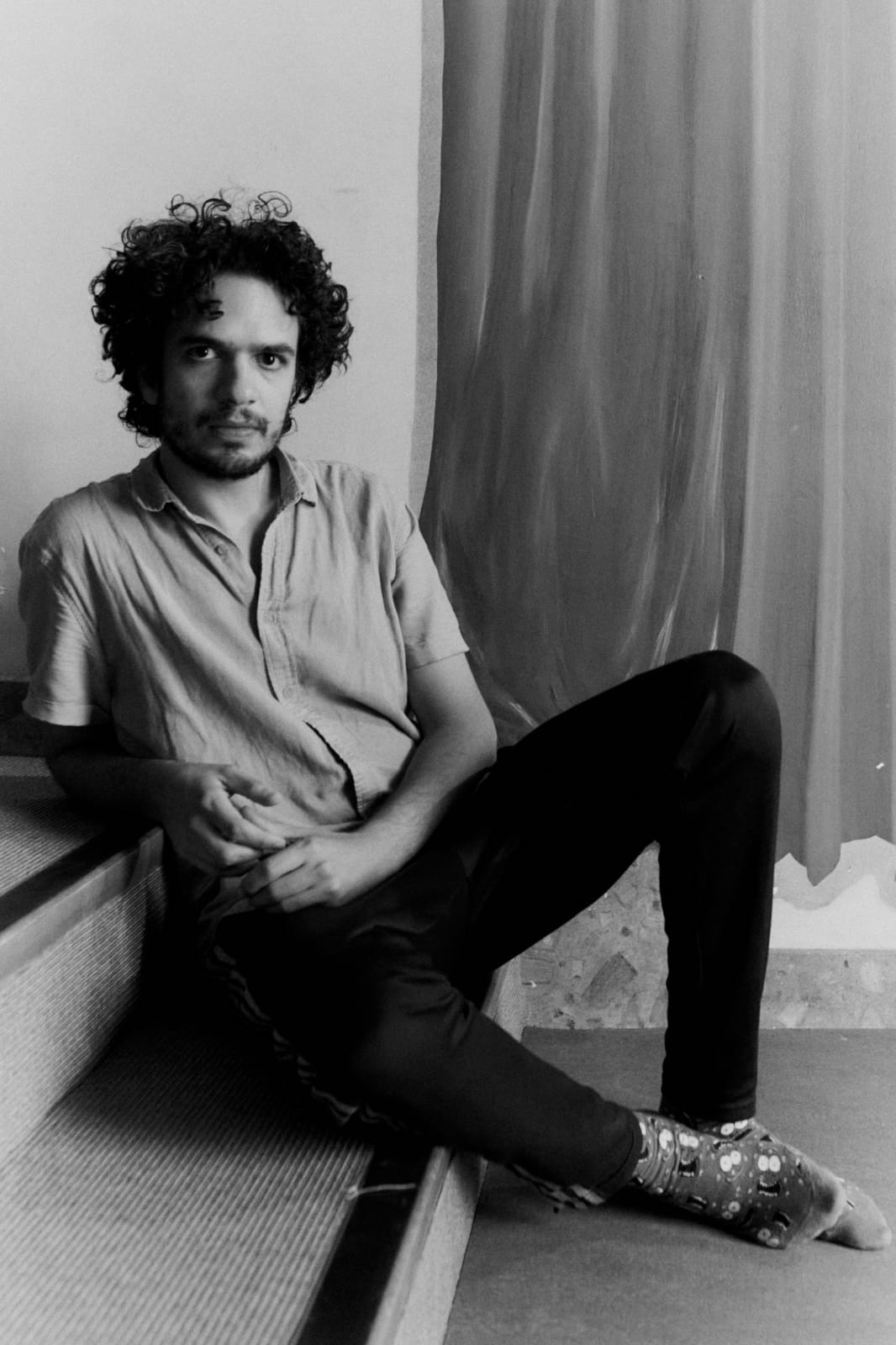

Amir Bresler works with a lot of different artists, but regardless of style, he’s sitting in the pocket

Drum solos are not usually my thing, but check this out from Israeli drummer, Amir Bresler. He obviously knows his way around a kit—the polyrhythms are sick—but, even better, it’s musical.

Musicality is central to Bresler’s approach. It’s why he’s a fixture of the small, but mighty, Israeli jazz scene—his curriculum vitae is a who’s who of Israeli luminaries like Avishai Cohen, Omer Klein, Gilad Abro, and Daniel Zamir—although he’s also an in-demand player in myriad other creative projects as well.

That musicality also explains why Bresler’s the de facto house drummer for the sometimes-experimental-somewhat-electronic-always-chill-label, Raw Tapes. He doesn’t play on every Raw Tapes session, although you would be forgiven thinking he does when browsing their catalog. His other efforts, which are often collaborative, include things like his West African-influenced project, Liquid Saloon, the low key, keyboard-heavy group, Apifera, as well as his solo outings, which often feature friends. “I really like to play with people,” he says in our interview below about the pleasure of collaborating versus the frustrations he felt doing remote recordings while on lockdown. “The joy is when playing with people. There is no substitute for it.”

That joy is palpable in Bresler’s music, and was obvious when I spoke with him recently from a studio he shares in Tel Aviv. We talked about the roots of Israel’s bourgeoning jazz scene—which he’s been a part of for years—his pleasure in discovering the laidback Raw Tapes community, his voracious appetite for 1970s-era lo-fi international grooves, and how he managed to stay super-busy and productive despite the pandemic.

What’s your background and when did you start playing drums?

I started drums when I was 13. I started it randomly. I wasn’t that much into music. I didn’t know what were the drums and what were the guitars. I wasn’t into it [laughs]. But then my father asked me if I wanted to play something, and I said, “Maybe drums?” My neighbor had a drum set, so I checked it out. Then I fell in love. Really fast, I knew it was my thing.

Do you go to a performing arts high school?

I went to the Thelma Yellin High School in Giv’atayim. It is a nice place to be, and with great people. It’s like heaven for a high school. But it’s not fancy. Everything looks ok, but the teachers and the students were high quality. The people there were very powerful, more than the facilities. People come from all over Israel, which means they have to be serious about what they’re doing. It’s not like going to the music conservatory close to home to have some fun. They come because they really want to make it happen.

Did you start gigging while you were in high school?

A little bit, yeah. When I was in the twelfth grade, I started really gigging with some cool people—it was always with cool people—but I started playing with some of my teachers, and that was a big deal for me.

Did you serve in the IDF?

I was in the army band.

How does that work? Do they have you doing everything, from parades to jazz?

We played like a regular band, and played a lot of covers. We had a playlist of popular Israeli songs. It wasn’t like we did our own compositions. I also recorded playbacks [backing tracks] for singers. Some of the other bands only had singers, and they needed some backing tracks. I played the drums for those. It’s very nice doing a lot of recording sessions like that when you’re very young. Nowadays, maybe the music is more programed. For my reserve duty, I went once and recorded a song for a backing track. Then that was it. I finished my army service for good [laughs]. That was my reserve service [miluim/מילואים].

The Israeli jazz scene is thriving these days. How did it get like that? It’s not like growing up in New York where you’re surrounded by African-American music and culture.

It started with a special movement of guys who lived in New York in the 1990s. People like Amit Golan. For me, he’s the head of the new movement. He was a great teacher and a very important man. He played piano, and the jazz tradition to Israel. He brought lots of energy and was very passionate, and that made people get into jazz, and also to dig the right stuff. He was really at a different level from other people—from teachers before him—and because he was so strong, lots of teachers got his energy and became great teachers as well. He died about 10 years ago. He was such a great man and he died while playing basketball with his students. He had a heart attack.

What did he bring back, besides his passion?

We listened to so many records. He was little bit extreme, and his focus was the 1950s and ‘60s. If it was from the ‘70s, it wasn’t the real deal for his taste. We were really focused on the old stuff. The objective was to get the roots of jazz, and not just be a version of the new stuff. It was to try to understand the meaning by digging the roots.

What kind of stuff, like ‘50s-era Coltrane, Monk, Mingus, Miles?

Sure, and also Lester Young, some singers, people like pianists Bobby Timmons, Wynton Kelly, and also earlier stuff like Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker. It was very focused, and maybe that was the key. Checking out that period of time was very important for us, and I think it really influenced the jazz scene in Israel. People ask me about the Israeli jazz scene a lot—how have Israelis become such great jazz musicians—and I don’t have a really bright answer. Part of it could be a matter of luck. Amit Golan was part of it, and we were lucky to have him. I am not saying that without him it wouldn’t have happened, but it’s almost like that. We were lucky to have someone who brought the whole thing here and made us really understand and appreciate it.

Yakir Sasson (Quarter To Africa) told me that there is an Israeli sound, which incorporates some of the Middle Eastern edge, like makams and things you hear on the street.

Yes, for sure, if you walk in the streets it is different than walking in the streets in Europe or in the States. You hear so much music that has its roots in Arabic music. Arabic, or Jewish music from Arab areas like Yemen, Morocco, Syria, and Lebanon. Muslims and Jews both love this kind of groove in the music. You hear it on the street, and you hear it a lot. Also with some Israeli pop stars—some of the biggest pop stars—incorporate this kind of music. It’s more like Middle Eastern music. It’s not American. Some of the mainstream artists do sound very American—or something in between—but there are also a lot of artists who are rooted in Middle Eastern music. It really effects everybody. I am actually learning the oud now, and I am really starting to dig some Arab music from all over the world.

What is your relationship with Raw Tapes Records? It seems like you’re on every recording.

Raw Tapes is a nice story. I met Yuvi Havkin, he goes by the name, Rejoicer, and he’s one of the people who runs the label. We quickly became very good friends. We met and shared a lot of music together. It was very fresh for me to record music that wasn’t jazz or rock. It was more experimental and hip hop. It was like jazz in a way, but more synth-based. I fell in love with the situation, because it was stuff that I needed. I needed this, and I met lots of people because I met Yuvi. He has great friends, and now we are like a very big—I don’t want to say crew—but it’s lots of friends who are part of this Raw Tapes thing. A lot of great musicians got into it and record albums here. It’s a great thing, and I really love the way it works.

Raw Tapes has a sound, or a vibe, which is very chill and laidback.

I think they also have opened up the vibe. I recorded an album for Maya Dunietz, who is a great piano player. It was released a few weeks ago. It is more like a jazz trio in a way—piano, contrabass, and drums—Avishai Cohen, the trumpet player, is on it, too. It’s totally different from some of the other stuff on Raw Tapes. There’s also iogi, which is different from the other music on there. But it doesn’t get very intense on the records. Not like noisy stuff. The energy is more laidback. It never shouts at you.

Is there an audience for that kind of music in Israel? Is it still considered underground?

It depends. It’s not like they are big hits, but some of the Raw Tapes releases will do well on playlists on Spotify and places like that. So we have lots of listeners, that’s for sure, but it’s not like we have very big shows here in Israel, although they’re also not really small. It’s very cool.

I am asking because I am curious if independent and creative artists able to survive in Israel, or do you also have to have a day gig or play weddings or things like that?

Me, for example, I am playing with some stuff for Raw Tapes, but I am also playing with other artists in Israel, and lots of jazz, so I don’t need to get another job. Most of the people I play with these days don’t have a side job.

The scene is supportive.

Somehow we survive it. It’s cool, but it’s not like the government helps us. The government has nothing to do with culture or financing the kind of stuff we do. But we’re trying to make it happen anyway.

Is it also important to cultivate an audience overseas?

That’s true, if you want to make something happen with this kind of music, you can’t only stay in Israel.

A lot of people associate Israeli music with Arabic, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern musics, but you’re also very close to Africa. Do you hear much of an African influence as well?

I am not sure, but that’s not something you really hear. I don’t think we have a lot of influences from African music. You will find people really interested in Ethiopian music, because we have a lot of Ethiopian people in Israel. Sometimes, when I’m walking in the street and see someone from Ethiopia or Africa, they’ll be listening to traditional music from their country on their phones. It’s very cool. But you can’t say them. It’s not everybody, but what you see sometimes is very cool. It’s hard to generalize like that, but that is part of the experience of walking along the streets and, say, hearing Ethiopian music coming from an Ethiopian club. But there’s not a lot of it.

I got into African music after I heard Tony Allen [legendary afrobeat drummer, known for his long association with Fela Kuti]. I didn’t only listen to Tony Allen, but because of Tony Allen I started listening to lots of records from Africa, and it has been a big influence on me. I also like the sound from Somalia. There is a great Somali called the Dur-Dur Band. They are so funky. It is like the best funky stuff, and there’s something so strong about the groove. I like a lot of old African records from the ‘70s. It’s drum sets and guitars, and I like the rough sound more than the new [electronic] sound. Sometimes when it’s the new sound, I am not feeling the same vibe.

Are you incorporating that into your music?

I started Liquid Saloon with keyboardist Nomok (Noam Havkin) and trumpeter Sefi Zisling. I said that I wanted the groove to be [central, and to be authentic]. I want to it to be original, and not because I listened to a lot of African music. We’re not trying to be exactly the same. However, when we do covers—we have a special show for covers, Fela Kuti covers and things like that—so there we are really trying to do it just like the recording. But with Liquid Saloon, we’re trying to have our own sound. It’s our compositions. We’re not trying to write Fela Kuti-style melodies or something like that. We’re doing our own thing.

Is Liquid Saloon just the three of you?

On the first record, I played drums, bass, and guitars. For the next record, which will be released next year—it’s ready—it’ll also be with Elyasaf Bashari (bass) and Roi Avivi, who is a great guitar player. They are now also a part of the recordings.

It looks like you were busy over corona. Did you live in your studio? How were you so productive?

We just tried to do something. We didn’t want to stay at home watching Netflix. It was a lot of fun. For me, it was a really good time. I know it was a very bad time around the world, but for my life’s work, it was a very special time.

Were you able to have other people come over and play, or did you do things remotely?

I did a bit remotely, but I wasn’t that into it. I really like to play with people. Sure, we can make something nice remotely, but the joy is when playing with people. There is no substitute for it. We weren’t that remote in Israel. We saw each other a lot.

The restrictions were relaxed a lot last summer.

It was a good time, and there were no shows in the evening, which was very cool for the relationship.

Are gigs coming back now?

All the way, there is something almost every night.

What do you have coming up?

I finished my album. I recorded an album in the north of Israel, in Ein HaShofet. A friend gave an auditorium. He told me, “Come and sleep in the kibbutz and we’ll give you food and everything you need, just bring the equipment and you can record in the auditorium.” It was a very special place with a special sound. It is going to be released in January 2022, maybe before.

Are you the only musician?

No. Every day some other friends came and played. It was a very special time because it was so focused like that. One week—or more like five days—I was doing only that. There was nothing around me, just nature and the studio.

There’s also Apifera. That band is me, Rejoicer, Nitai Hershkovits, and Yonatan Albalak. The lineup is two keyboards, and then bass or guitar depending on the song. It’s a new band and we released an album for Stones Throw Records not long ago. It is another project that I am apart of, and there will be some new stuff soon because we are always recording and mixing and mastering.

All that music is up on Bandcamp, and other online outlets, too?

Yes. I don’t remember what else, but more stuff is going to be released soon as well.

From The Archives: Everything’s In The Hands Of Heaven

Nissim Black talks about his on-going journey, the evolution of his musical style, and the importance of being a positive role model.

Go here to read the full interview with Nissim Black.

Subscribe To Our Premium Tier. $5/Month Or One Year For Just $50

Subscribe now to our premium tier. It’s just $5 a month or $50 for an entire year (that’s two free months!).

The premium tier does not replace the great content you already receive, rather, it gives you even more.

Specifically, paid subscribers get:

Deep, probing essays about the spiritual nature of music.

Incredible curated playlists. These playlists include more than just music from the artists featured in the Ingathering, but also things we stumble upon in our research, and amazing things we need to share. If you’re a paid subscriber, you’re someone who needs to hear this.

The opportunity to support the Ingathering. The Ingathering is fun to produce, but it takes a lot of effort and time to research and write. A paid subscription is an amazing way to show your support.

Become a Founding Member. If you love the Ingathering, and you’re looking for a way to show even more support, become a founding member. The suggested founding donation is $180. You can give less if you want—as long as it’s more than the cost of an annual subscription—and obviously, you can always give more. The amount is up to you.

If you’d rather just give a donation, you can do that, too. The Ingathering is a project of Vechulai, a registered 501(c)3 tax exempt organization. Go here to donate and learn more. You can also Venmo us @Vechulai

If you don’t want to be a paid subscriber, that’s not a problem. Stay a free subscriber and keep enjoying the great content you already receive.

As always, if you have any questions, hit reply and we’ll get right back to you (or email us at: jewishmusicandspirituality@gmail.com).

Thank you being a regular reader and part of the Ingathering family. Your support at whatever level—founding member, premium subscriber, or free subscriber—is invaluable, and we can’t do it without you.

Thank you!