Café Feenjon And Other Adventures

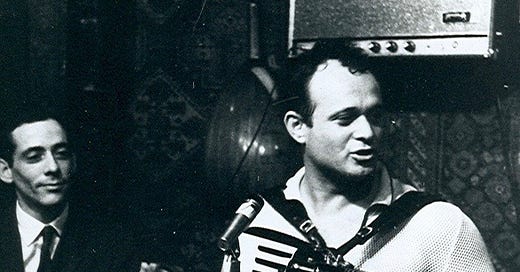

Avram Grobard talks about the Israeli expatriate community in 1960s NYC, recording and performing with the Café Feenjon house band, fusing disparate musical styles, and his mission to Sinai in 1973

In the 1960s, New York City was home to a thriving Israeli café scene. The places were small, and their main attraction—in addition to hummus, falafel, and coffee—was the opportunity to speak Hebrew and meet other Jews. Some of the cafés had live music as well, which was usually a blend of Israeli, Greek, Turkish, Armenian, and other Mediterranean styles, and for those in the know, the best music was at the Café Feenjon.

Café Feenjon started on 7th Avenue as an after hours place for working musicians, before outgrowing its space, and moving to Greenwich Village. The house band—once the venue became more established—worked seven nights a week and played until four in the morning. Each member sang, and the lineup usually included accordion, dumbek, guitar, and oud. They recorded a number of albums as well, including their exceptional, self-titled debut, which was recorded live in the club in 1964. The band fused Yiddish folk songs with Mediterranean instrumentation, sang romantic Italian ballads, jammed naturally in odd meters, and helped pioneer the organic, multicultural fusion of those near-Eastern musical styles.

“We blended it together, which was Manny Dworman’s idea,” Avram Grobard, the house band’s original accordionist, says in our interview below. Dworman owned Café Feenjon, and played oud in the band. “It was his idea to blend Jewish music together with Greek, Arabic, Turkish, and Armenian music. He blended all these Middle Eastern sounds. He took Yiddish songs and we made them sound Oriental. That was his thing. He started all this music, that blend, and he was the crazy glue that put everything together.”

Grobard left Café Feenjon in 1967, and opened his own establishment, El Avram, on the eve of the Six Day War. We discussed his experiences as an Israeli in 1960s-New York, starting the Café Feenjon’s house band, the era’s folk revival and how that included an embrace of traditional musics, the early days of El Avram, and the impact of his visit—along with Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach—to Israeli troops fighting along the Suez Canal during the Yom Kippur War.

When did you start playing music?

I was 10 years old at the time of War of Independence, and I started playing the accordion when I was 11 or 12. My first appearance was at my Bar Mitzvah. I remember the song I played.

Did you start singing at that time as well?

No. I played accordion. I had a band and I faked singing. Later on, I faked playing the accordion and I sang [laughs]. I used to accompany singers in Israel. I was a young kid—17 or 18—and I worked for cheap. They gave me a few dollars to accompany them. After that, I was with a group from Egged, the transportation company. They called it a Galgal group. I performed with them, and then, when I was in the army, I formed a band in the air force.

Did you do your service as a musician?

I served as an electrician, but in order to not have to wake up in the morning, or do guard duty at night, I volunteered to form a band. The band was used to play for all occasions in the camp. After we finished with the army, I continued with this band and we played all around the country. We were very famous. We were called, Matai Omanim, or the Red Shirts. We played for beauty contests, and at clubs. Sometimes I couldn’t find the right note, so I sang it. Little by little I found out I had a good voice.

Live performance of the Feenjon Group filmed for Irish TV. Footage of the band starts at 1:25.

How did you end up in the United States?

By mistake. I went to visit the U.S. Somebody met me in the street, and said, “Somebody is opening a café and they are looking for an accordion player.” I said, “But I don’t have an accordion.” He said, “Someone in my apartment plays the accordion. Let’s ask him if we can rent it for the weekend.” That person said I could rent it for $15. I got paid $20 for the week. So I got $5, and hummus and falafel for free. That’s how I started. The café was called the Cellar.

Are you saying that you didn’t move the States on purpose?

I did very well in Israel. I left my scooter downstairs in the apartment. I was supposed to go back, but everything happened accidentally. A few days here, a few days here, and I made a few dollars. I worked at the Cellar, and after that I worked at Casit, and the Café Tel Aviv, Café Feenjon. There were so many places. Tamar. Exodus. There was also a night club on 72 Street called Sabra at that time.

Why were there so many Israeli clubs in New York?

They were cafés, not pubs. They didn’t even have a liquor license in those days. They didn’t apply for it. Hummus, falafel, and coffee. People would come, and they wanted to get together, to meet. Shlomo Carlebach used to come to Cafe Tel Aviv. He used to sing the songs that he wrote for me. He’d say to me, “Avramale, how is it?” I thought, “A Rabbi with a guitar?” I came from an orthodox home. It didn’t look right to me. But we became very good friends later. He was an excellent friend. As a matter of fact, I went for Yom Kippur to listen to his Kol Nidre at his synagogue on 80 Street. Many places opened, and the reason was that a lot of Israelis came here. At that time, we had Israelis who wanted to stay in America. They looked for American women to marry to get a green card, in order to stay.

Were these clubs all over New York?

They started at 92 Street. The Cellar was on 93 Street. Casit was 96 Street. Cafe Tel Aviv was on 72 Street. Café Feenjon opened on 7th Avenue. It was a small, little place. Those of us who worked—the musicians and singers—after work, we would go to Feenjon. Feenjon was open until the morning. You’d sit around the tables—there were about seven or eight tables—and Manny Dworman was the owner. All the musicians from the places on 8th Avenue—and there were Greek, Armenian, Turkish, and Jordanian musicians as well—and we would sit around the tables and play music and improvise. Manny would give us hummus. The belly dancers came from 8th Avenue and danced in the aisle. It became so big that he had to move to another place. Manny found a place that was called the Black Pussy Cat, at 105 MacDougal Street. The place had two rooms, the regular room and a second room in the back. He had flamenco singers in the back room and the front room was like the other place on 7th Avenue. People sat around the tables, played music, and sang. There was a flute player, a dumbek player, and many other musicians. And then I bought a new electronic accordion called a Cordovox.

Is that the accordion with the enormous amplifier?

Yes. Huge. I used to leave it at the hotel where I lived, and I practiced in the hotel. But people complained. So I asked Manny, “Can you give me the back room to use once a week at least?” He said, “No. I have flamenco.” But finally, I convinced him, and he gave it to me to play on Thursday nights. I started playing in the back room. People came from the front—nobody was in the back room, it was empty—but they heard music, and then another guy came with a dumbek and joined me, then another guy came with a guitar and played with me, too. More people started coming in, and little by little, it started building up. I had so many people, but there was no stage or nothing. I took some soda boxes and I made a little stage. There was a little light that I turned on us. Three or four of us would play, people came in, and then Manny said, “What are you doing?” At that time, you were not allowed to have more than three musicians play, and no dancing. You needed a cabaret license and they sent inspectors. He was afraid to get a summons. He didn’t want me making it like a stage, but playing around the tables was ok. Eventually, we convinced him to put up a stage, and people started pouring in.

Where were they coming from?

From Brooklyn, and from all over. They also still came from 8th Avenue, when they finished working at four o’clock in the morning—the musicians and belly dancers—everybody came. They were dancing in the aisle. The place had lines around the block to get in, and people were fighting for a seat.

Were you still playing in the back room?

All in the back room. The front room was nothing, it was a waiting room to go to the back room. They took your name and you had to wait until somebody left. We did fantastic there. It was such an atmosphere, but we worked from nine o’clock in the evening until four in the morning, nonstop.

Was that your main gig? Did you only work as a musician at that point?

Yes. I was very friendly with Manny. He listened to me. He was a taxi driver, and he also taught Hebrew for a while, but he was a very smart man, very intelligent, and he played the mandolin with us. Later on, he moved to the oud. It was really a lot of fun.

The music was “Israeli,” but those Mediterranean styles—like Greek, Balkan, Turkish—have a lot of similarities. What are the commonalities?

We loved the Greek music. Israeli music in those days, it was very similar—oom pah, oom pah—it was happy music. We blended it together, which was Manny Dworman’s idea, to blend Jewish music together with Greek, Arabic, Turkish, and Armenian music. He blended all these Middle Eastern sounds. He took Yiddish songs and we made them sound Oriental. That was his thing. He started all this music, that blend, he was the crazy glue that put everything together.

Grobard with Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach at El Avram

Who sang? Was it whoever knew the language the lyrics were in?

First was a Yemenite guy, named Hevron Levi. He played the dumbek and sang in fake Arabic. When he sang in Arabic, he used Arabic curses. But then someone who spoke Arabic heard it and said, “What is this? This is crazy?” Then Manny hired a Greek guitar player, Taso Mavalis. He had a very soft, very nice voice. He was a gentleman and always came in a tie. He was well-dressed and well-groomed. We had other guys, too, Ed Brandon, Jerry Safer, different people joined us and little by little, the stage filled up with people.

The 1966 self-titled album, Café Feenjon, was that recorded live in the club?

That was the first one. A religious guy from Borough Park [Brooklyn] asked if he could record us. That was in 1964, and stereo just came out. We recorded it live. What you hear was in the club itself. The atmosphere is unbelievable. The recording quality is not as good, but the atmosphere is wonderful.

How many nights did you take to record it?

One night, it was done in a few hours. Don’t forget, we played every night. We knew what we were playing. We just had to record it to get the right sound. It’s not that we had to practice or decide who was going to play what. We knew. Although we were fighting, “How many songs do I get to sing?” We decided that everybody sang three songs. That recording was a wonderful evening. I still have it in my head. It was wonderful. The people participated, too, and they were all customers out there. Nothing fake is there.

Did you clean it up in the studio afterwards?

Isaac Hager was the name of the guy who recorded us, and he took care of it. The name of the record label was Fran Records, which was his wife’s name. We never got a penny out of it. He promised us money, but nobody got paid.

That’s the best of the Feenjon recordings, but it’s the only one that isn’t available. Why hasn’t it been reissued?

He wanted to sell me the master, actually. He wanted a thousand dollars at the time. I told him, “We didn’t make any money. You were supposed to pay us 35 cents a record. We never saw one penny.” He said, “I cannot sell it. I can sell you the master and you can release it.” I decided not to buy it.

Did you tour, too, or did you only play at the Café Feenjon?

We did a Town Hall concert, which was a big thing. We did concerts in different places, like the Rheingold Festival in Central Park. But Town Hall was the biggest thing at the time. We sold it out, too. It was a thing. I am telling you, every Saturday, people stood in a line around the block to come in.

Musically, were you a part of the 1960s folk revival, and was that part of the interest in Israeli music?

Of course, it was the time of the Hootenannies that we’re talking about. Sometimes, I would take the accordion to Washington Square Park—and the guitars—and play on Sunday afternoon. It was a very big movement at the time.

The music that’s called klezmer today, did that fit into the style of music you were playing back then?

It was different. Klezmer is more the Polish, shtetl—from Europe music. There was no klezmer at this time, it developed later on.

When did you open your place, El Avram?

I worked at Café Feenjon for quite a long time, from 1963 until 1967. But Manny was an ego maniac, and we had an argument, of course. One day I said, “I am going to open my own club.” I found a place in Sheridan Square that used to be El Chico. El Chico was a very famous Spanish nightclub—in the movie, The Apartment, Jack Lemmon says, “Let’s go to El Chico.”

Was El Avram the same type of place as Café Feenjon, did you have a band and a similar crowd?

I changed it a little, and I made it more modern. I also had American music and dancing, and I had a cabaret license. My partner was Bob Janoff, who was also an insurance investigator. One day, Bob brought over a Jewish owner of an insurance company—his name was Al Sanders—and Al said, “My daughter sings like Joan Baez, will you let her work here?” I said, “It’s an Israeli club—Jewish, Russian, Turkish—I don’t need an American singer. It doesn’t work.” He said, “I’ll pay you to pay her, and I’ll fill the place. I’ll bring all my agents that work for me.” It was a big insurance company, so what did I have to lose? I said to bring her—she was an excellent singer by the way—but she didn’t fit. It was a Tuesday when she sang, and a guy from the New York Times walked in. The place was mobbed—it was all insurance agents—and he couldn’t believe it. He wrote me up in the New York Times, “Olé Becomes Oy Vey.” After that, people from all over the world started pouring into the club.

How did views change after the Six Day War?

I opened in June 1967, and a week later the war started. I was in the Israeli reserves and I was supposed to go back to Israel. I thought, “I just started the club, what am I going to do?” But I was lucky, it was only a six day war.

Otherwise you would have gone back?

Yes. Everything came from God. When Jerusalem was conquered, my place became the hit of New York. Everybody came out. It was euphoria after Israel won this war. I had a line around the block. People begged to come in. It was amazing.

How long did that last for?

A long time. My audience was mostly Jewish—and Jews also come from Iraq, Iran, or wherever—but I had people coming from all over. As a matter of fact, the New York Daily News came one day and saw—we had a big round table—and they said, “Why can’t the United Nations come here and see how music connects all those nationalities? Palestinian, Arab, Egyptian, Russian, Greek, Armenian—all sitting together, playing music, and being happy.”

Grobard entertaining Israeli troops during the Yom Kippur War

Did you go to Israel for the 1973 War?

For that war, I went to Israel, and I entertained the troops in the Sinai Desert. I put together a band and the air force gave us a small airplane, a piper plane, and flew us from one unit to another. We used to play for four or five people near the anti-tank and anti-cannon Howitzer, that’s where we used to entertain. I remember the plane. We asked the pilot, “Why are you flying so low?” He said,” Because I don’t want to be hit by a missile.” That experience changed my outlook to life, because when I was going from one foxhole to another foxhole, I saw hundreds of dead Egyptians, lying in the desert. That changed my whole attitude. I thought to myself, “His mother in Cairo doesn’t even know that he’s here.” They hadn’t collected the bodies yet. I felt and I looked at life differently. I changed my mind completely about what life is about. I felt sorry for them.

How did you change?

I became a better person. I was very aggressive before. I calmed down and became a little softer.

How close were you to the front?

I was at the Suez Canal. On the way to Sinai from Israel itself, I met Carlebach. He came over, too. At the air force base, at Tel Nof, he performed for them, and he drove them crazy, “Am Yisroel Chai.” I don’t know what he did to them. Seeing him live you cannot forget it, you know?